Enabling and Natural Consequences: Two Sides of the Same Coin

"Isn't Housing First just enabling people to continue their negative behaviors?” This question is often asked when people first hear about the Housing First philosophy or the harm reduction principles that are so vital to our work.

Related sentiments, such as, “Shouldn’t we be focusing on the people who can prove they’re ready for recovery?” or "Why should my tax dollars go toward those people?" carry the assumption that, with all else being equal, "those people" don’t work as hard and are undeserving. These statements both mistake our social systems for a functioning meritocracy and incorrectly assume that the only way for people to get well is to face natural consequences, which can sometimes be code for suffering.

Our answer to these questions is, “Yes, Housing First and Harm Reduction are enabling.” Housing First is about enabling dignity and self-determination. Stable housing enables a person to have their basic needs met so they can achieve their goals. Who among us could be our best selves without a roof over our heads?

Enabling, as typically defined, is a holdover from a previous time. Treatment in the mental health and substance use spaces is littered with other examples of outdated concepts and approaches: “mental health and substance use have to be treated separately and sequentially,” “the clinician is an expert who leads the treatment process,” and “an individual has to prove their housing readiness through sequential treatment.” In fact, a traditional treatment-first program, requiring participants to prove their housing readiness through abstinence from drugs and alcohol and participation in mental health treatment, achieved much lower housing retention rates (47%) as compared with Housing First (88%) over a 5-year period.

This outdated concept of enabling places extremely high expectations on people to commit to self-actualization at all times, without a break, while fighting for survival in systems that are stacked against them. Incredibly, some people are able to achieve their goals in spite of the odds. But we shouldn’t require frequent brushes with death to afford someone the stable conditions that most of us need in order to make real changes in our lives. It is time to let go of this outdated and harmful concept.

For those who label harm reduction as enabling, some also believe that people who use substances and those who experience mental illness and homelessness must face “natural consequences” in order to make the choices that we think are right. However, the line between when we should let people face those consequences and when we should directly intervene to mitigate harm can be murky; the line changes from person to person. Even champions of Housing First and harm reduction debate how much to intervene when a client is not taking psychiatric medications and is at risk of eviction due to disruptive behaviors in their apartment building. And the decision to re-house someone who lost their apartment after selling the radiators can be challenging.

People in vulnerable groups experience major consequences for their actions and choices every single day. Yet, natural consequence is a term that is often weaponized against people, reinforcing existing stigmas. It is a term that is wielded when a person crosses the invisible line between acceptable and unacceptable behaviors. Sometimes, the term can even be a shield for our implicit biases, giving us an easy way out of a difficult decision regarding care and treatment. For example, wouldn’t it be easier to discharge a person with significant mental health symptoms into an assisted living facility because they are at risk of starting fires when they cook on the stove? Wouldn’t it be easier to discharge a person from the medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) program when they are known to be selling their Suboxone?

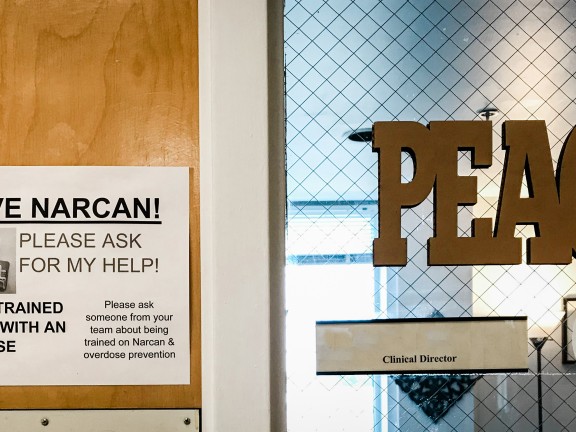

When we buy into the Housing First principle of “participant choice and self-determination,” we can let go of the distinction between which consequences we will allow and which we will protect against. If a harmful natural consequence can be mitigated, it should. However, a person’s choices are their own. Our goal is to provide the tools and information to mitigate harm whenever we possibly can, as many times as needed.

It may be true that some individuals hit rock bottom and find the motivation to make different, health affirming choices. But for many, the path to rock bottom, if it ever arrives, is a long road of unnecessary suffering. Individual choices do not define recovery; most people don’t choose homelessness. Usually, support and resources create the space for individuals to make safer choices.

Housing First allows treatment providers to be patient, giving room for people to pursue their recovery in the way they see fit. Once a person has a home, the urgency and desperation of scrambling for survival can be removed, creating space for people to move incrementally toward recovery. I guess you could say recovery is a natural consequence of having our basic needs met.

Source: Gulcur, L., Stefancic, A., Shinn, M., Tsemberis, S., & Fischer, S.N. (2003). Housing, hospitalization, and cost outcomes for homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities participating in continuum of care and housing first programmes. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 13, 171-186.